"But you're not really published, right?"

Or, how to be punk when you're not.

When I entered the independent publishing arena, a common question (or accusation) was, Isn’t this only high-tech vanity publishing?

That’s not entirely honest, though. The way the question was usually phrased to me was, “But you’re not really published, right?”

When I mentioned the stigma of self-publishing to Sarah Meckler of the GSMC Book Review podcast, she offered an interesting observation. “I was hearing that a few years ago,” she told me. “I don’t hear it so often anymore.”

Why did the stigma shift between 2015 (or so) and today? I see it as a similar shift in attitude between 2000 and 2005 with online-only media (blogs, e-zines, web journals, and so forth). In the early days, a political blog wasn’t “real” because the blogger wasn’t backed by a major newspaper or magazine.

Over time, well-known traditional writers would go online-only, sensing the opportunity afforded by self-determination (and collecting money directly sans a middle-man). And, online-only writers who’d gathered a sizeable audience would pick up column placements with traditional magazines and journals. All of this served to normalize online political writing.

By 2005, the so-called “pajamas media” was being seen with more respect and an understanding of what it could, and could not, bring into the national conversation. From there sparked the explosion of online-only publishing empires, such as Gawker Media and Bartbreit.

While we haven’t seen publishing empires of the same magnitude with e-books, there’s certainly been an explosion of activity. One estimate believes there are over 6 million e-books for sale on Amazon, and project there will be 9 million by the end of 2021. Big-name authors have jumped into the fray, sensing the financial and creative advantages of being able to sell their work directly to their audience. We’re also starting to see traditionally published authors who got their start publishing Kindle e-books. All of this churn naturally blunted the stigma against self-publishing.

But the stigma remains. Even the most die-hard of readers doesn’t follow the inner machinations of the publishing industry. The long shadow of traditional publishing lingers. It’s punk for a band to sell their home-recorded music on their web site; it’s desperation when a writer does the same.

(More so than with the movie or music industries, book publishing clings to a nineteenth-century business model of slush piles, snail mail, editor hierarchies, and professional agents. It’s changing, but the change has been glacial.)

Here’s my theory why the stigma against self-publishing persists, even if it’s draining off:

When people are evaluating the worthiness of a book, observe their criteria. Too often their focus centers on the book’s genre, cover, title, length, availability (paperback vs. e-book), or subject matter. The author’s name, gender, sexuality, race, political leanings, or (alas) physical attractiveness are often considered, overtly or subconsciously. The publisher’s reach, reputation, and “authenticity” (a local co-op versus an international corporation) are given play. The book’s reviews—the number of them, or where they’re placed—has a great deal of weight. Too often, attention is paid to everything except the words inside the book. It’s like people are looking for excuses not to read.

When this is the model for evaluation, anything that can be a trigger for immediate dismissal is valuable. For some people, self-publishing can be an easy way to set aside a book rather than consider it on its real merits.

Follow up to “Show me the data”

Previously, I griped about book promotion web sites not sharing their data with their paying customers (namely, me). I mentioned in passing BookRaid, a promo site that charges per-click rather than a flat fee. I couldn’t speak to their service at the time because I’d not used them, but I did have a promotion scheduled.

Well, that promotion went off, and I can report back on the experience. BookRaid reported (in real-time) the number of clicks my promotion received. I could then correlate that number against the number of books I sold that day (assuming none of the sales came from other sources—it’s a big assumption, but not one that BookRaid can correct).

With simple arithmetic, I can glean two interesting statistics from their data: (a) number of sales per click (the “conversion rate,” to use marketing lingo), and (b) my cost-per-click (or CPC—more marketing wonkery). Not bad.

So, while I’d certainly like more data from promo sites, kudos to BookRaid for taking a major step in the right direction. As I wrote, “If a site was looking to separate itself from the pack, data transparency would be a solid differentiator.” BookRaid is differentiating itself.

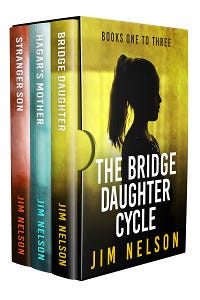

The Bridge Daughter Cycle is a Kindle box set of the first three books of my speculative-fiction series.

The series starts with Bridge Daughter, an alternate world of girls born pregnant who, at age thirteen, give birth to the real child and die. It’s followed by Hagar’s Mother and Stranger Son. All three follow the generations of a family struggling to comprehend and live with the biological fate this alternate world demands.

Bridge Daughter has received praise from Publishers Weekly, authors, editors, and readers.

The Bridge Daughter Cycle is available now. All three books are available separately in Kindle and paperback.

More information may be found at j-nelson.net